The sea is full of strange creatures. Parrotfish is no exception.

Its teeth are fused with a sharp beak, giving it a bird-like appearance. They are hermaphrodites and change sex during their life. And to sleep, some parrotfish wrap themselves in a mucus cocoon.

It may look strange and awkward, but this creature is a true hero of the sea.

Rising global temperatures, various diseases, and coastal development are killing the world’s coral reefs, iconic ecosystems that support a quarter of all marine life. By some estimates, the world’s coral habitat has been cut in half since the 1950s.

But without the parrotfish, the situation would almost certainly have been worse.

jenny adler

jenny adler

Parrotfish are basically caretakers who are very good at their jobs. These animals, which live in oceans around the world, use their beaks to scrape colonies of bacteria and algae from rocks as they cruise around coral reefs. If left unchecked, that algae can grow out of control, suffocating the reef and preventing new coral growth. This makes it difficult for coral reefs to recover after corals die in large numbers due to extreme ocean warming, for example. So corals have more room to grow where there are hungry parrotfish.

The problem is that parrotfish numbers have plummeted on many coral reefs, especially large parrotfish in the Caribbean. Meanwhile, other algae-eating animals such as sea urchins have also disappeared. Some scientists argue that’s why Caribbean coral reefs have failed to recover after climate-related impacts such as bleaching and superstorms. There is too much algae for the coral to regenerate.

On the contrary, these movements offer a glimmer of hope to an ecosystem that seems largely doomed. By protecting parrotfish alongside efforts to curb climate-warming emissions, countries may have a better chance of saving coral reefs.

If there’s one thing people know about coral reefs, it’s that they’re colorful—an intricate mosaic of blues, reds, pinks, and oranges.

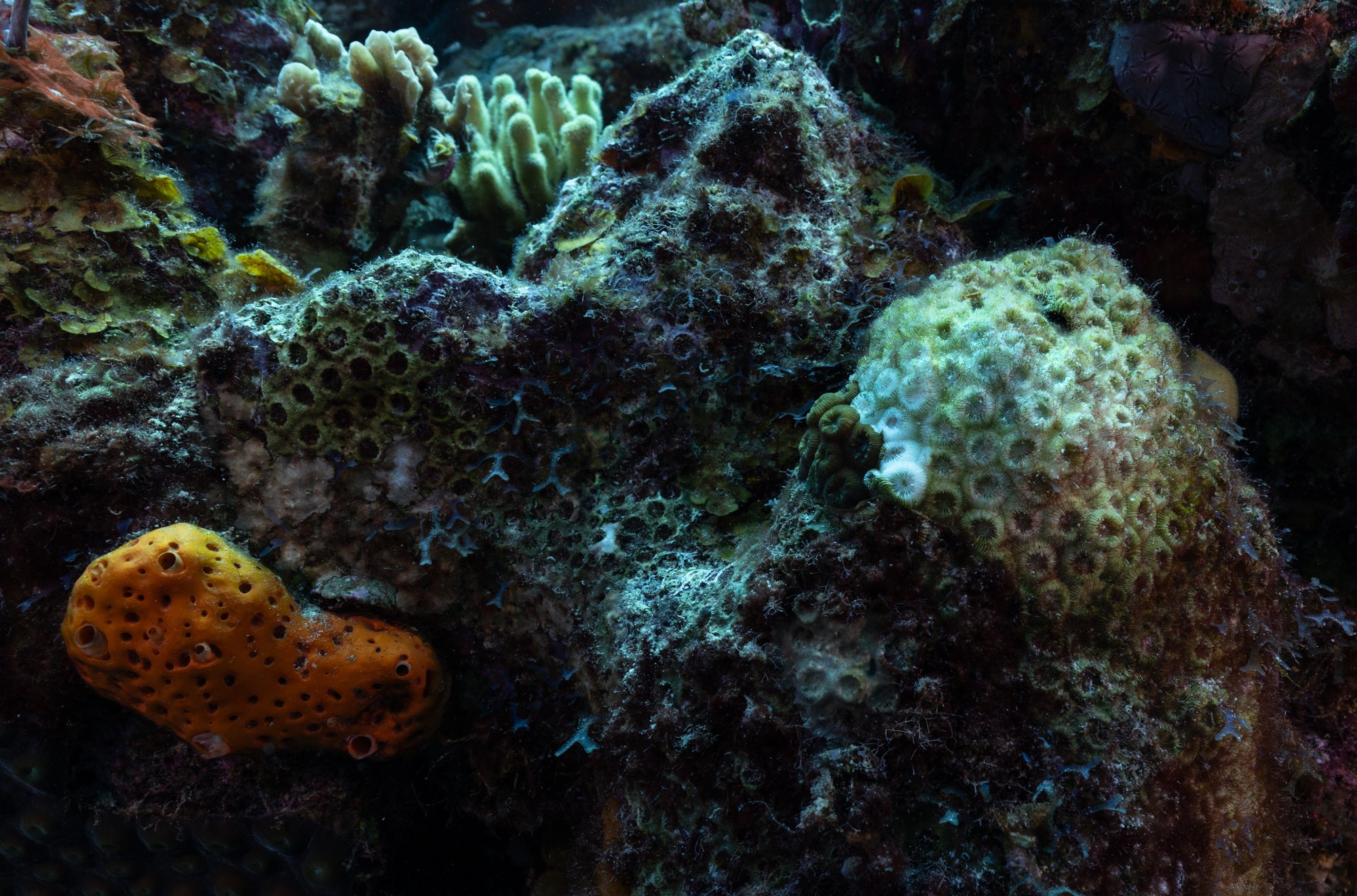

But more and more, only one color is starting to predominate: green.

Algae and seaweed are increasing in tandem with the decline in coral. When a coral dies, this green plant-like creature quickly grows on top of its skeleton. And when seaweed spreads, it can prevent coral regrowth.

Baby corals start their lives by swimming in the ocean and need a small amount of bare rock to grow into adults. When the ocean floor becomes covered with algae, coral larvae have nowhere to grow. Seaweed can also release chemicals that can be harmful to corals, and large algae growths can shade coral reefs.

“Coral’s biggest enemy is actually seaweed,” says Nancy Knowlton, a former Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History marine scientist and author. “Needless to say, coral reefs recover better if they don’t have to deal with large amounts of seaweed.”

Research shows that over the past 50 years or so, algae have grown on coral reefs around the world, particularly in the Caribbean.

Algae grows in human waste such as sewage and runoff from agricultural fields. This water pollution is rich in nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorous that algae need to grow. Therefore, when it flows into the sea, algae grows.

Additionally, long-spined black urchins, one of the most voracious algae eaters, began dying out in the Caribbean in the 1980s, likely due to waterborne pathogens. On average, Caribbean coral reefs lose more than 90 percent of their sea urchin populations within a few weeks, and the population has yet to recover.

Currently, the important job of shrinking algae, which helps corals grow and recover from death, is left to certain vegetarian fish, including parrotfish. In some parts of the Caribbean, parrotfish may be the only fish standing between relatively healthy coral reefs and those covered in noxious green filth.

Most of a parrotfish’s life consists of feeding on rocks and dead coral, grinding it into sand, and expelling it from its butt. Some beaches around the world are made primarily of parrotfish droppings.

It’s not entirely clear what parrotfish actually eat. Research shows that their main food source is bacterial colonies, including cyanobacteria and other microorganisms, that live on rock surfaces, often alongside more visible clumps of seaweed. . It is likely that parrotfish do not seek out seaweed itself, which is known to be detrimental to coral growth and recovery. But even as they feed on microbes, they end up removing them from the rock’s surface, says Andrew Schantz, a parrotfish researcher at the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

“Regardless of what they’re targeting, they end up removing algae from the reef,” Schantz told Vox. “That gives the corals room to come in and settle, or to grow and take up that space.”

This is similar to weeding a garden before planting seeds to give them room to grow.

This article was produced in collaboration with the Pulitzer Center.

This is the third story in an ongoing series about the future of coral reefs in the face of climate change and disease threats. This project was supported by grants from the BAND Foundation and the Pulitzer Center.

Read the first two stories here.

Many studies have shown that removing large fish such as parrotfish from coral reefs causes them to become covered with more algae, limiting the growth of some corals. For example, one study in Belize documented that when large parrotfish were present, there was less algae and more baby coral.

Similarly, a 2017 study found that nature communications By examining historical records of fish teeth and coral fragments, they linked parrotfish to coral reef growth in Panama. The study relied on reef sediment cores, tubes of material extracted from the ocean floor that contain layers of coral, shells, and dead animals. Using these cores, researchers were able to see how fast the reef was growing and how many parrotfish there were on the reef by looking at the number and shape of their teeth. .

Although studies like this support the simple idea that parrotfish help coral reefs, the relationship between fish and coral is complex and somewhat controversial in marine biology. For example, small parrotfish do not seem to limit the amount of seaweed they eat, even if there is a lot of it. Some studies failed to find an association with fishing restrictions. This is usually more parrotfish, and the amount of algae and live coral. Parrotfish also eat some live coral, but scientists don’t think this causes much damage to coral reefs.

“The influence of parrotfish on coral reef dynamics is not always clear,” says Joshua Manning, a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Colorado Boulder who studies parrotfish. “It’s safe to say that parrotfish are good for coral reefs.”

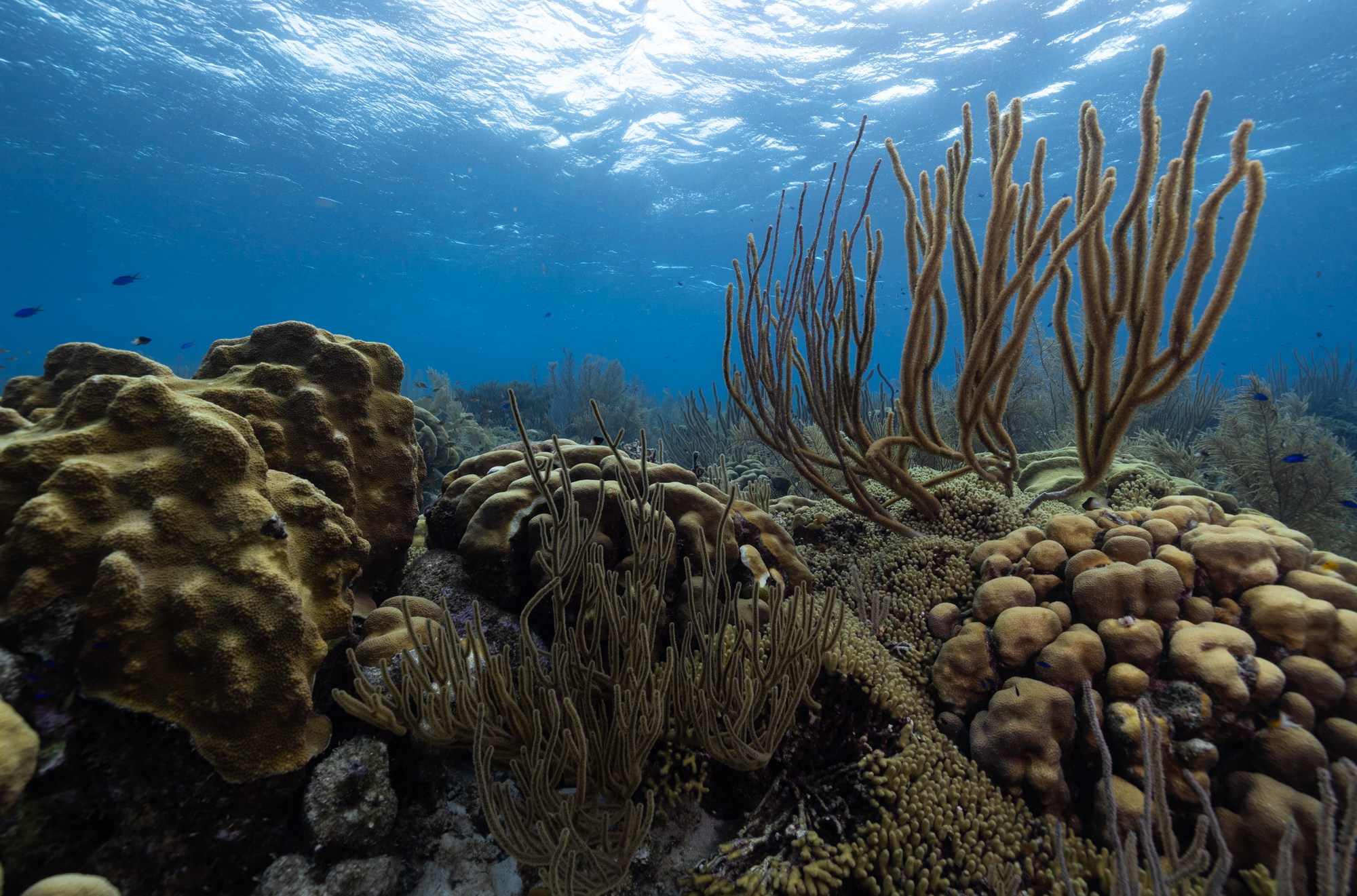

This is what a coral reef with lots of parrotfish looks like

People have been eating parrotfish for centuries in the tropics. Parrotfish are still common in many coastal areas around the world. (Google it and it says it tastes like sweet shellfish). Global population data are sparse, but it is clear that in some regions, such as Jamaica and Micronesia, parrotfish, especially the large parrotfish favored by fishermen, are declining due to overfishing.

These declines are almost certainly contributing to the increase in algae.

But there are places where parrotfish have been protected for decades, where they are still abundant and seem to be doing a good job. For example, spearfishing, a common method of catching parrotfish, has been banned on the Dutch island of Bonaire since the early 1970s. The southern Caribbean island just east of Curaçao also imposed a complete ban on parrotfish hunting in 2010. Although some of Bonaire’s large parrotfish species are still in decline, it now has at least twice as many parrotfish as most other Caribbean reefs. According to a 2018 report by the Dutch Caribbean Nature Alliance, a nonprofit organization.

jenny adler

jenny adler

All of these parrotfish help limit the growth of algae on Bonaire’s reefs, said Robert Steneck, a professor emeritus at the University of Maine who has been studying Bonaire’s reefs for more than 20 years. That, in turn, helps corals here survive, he says. In fact, while most of the Caribbean’s corals have been killed off by bleaching and disease in recent decades, Bonaire’s reefs are still intact. Some of it is still thriving.

Additionally, Steneck’s research shows that Bonaire’s coral reefs have been able to recover from large-scale die-offs in the past. Parrotfish inherently make this ecosystem more resilient, he says.

The reality is more complicated. There are many reasons why Bonaire’s coral reefs are healthier than other parts of the Caribbean, beyond the abundance of parrotfish. For example, the island lies beneath the path of most hurricanes in the Atlantic Ocean. Bonaire’s corals are also not as healthy as they once were. Bleaching has had a negative impact on coral reefs for many years. Then, in the spring of 2023, wildlife diseases began to spread, killing hundreds of hundreds of old corals.

There is little parrotfish can do about this growing threat. If corals continue to die and pollution continues to enter the ocean, coral reefs will become covered in seaweed. Manning said once that happens, there’s little that can be done to bring the parrotfish back to life. “At some point, the intensity and frequency of these disturbances will overwhelm parrotfish grazing,” he says.

Still, more coral reefs are better. Protecting coral reefs depends above all on policy and business efforts to reduce carbon emissions, but that doesn’t mean effective fishing regulations don’t help.

What the parrotfish makes clear is that the individual components of an ecosystem matter. If you remove any part, the system will start to fail.

“We need to protect coral reefs, even if it’s just to give them a chance,” Manning said. “As long as there are parrotfish, there may be a chance to at least extend the chances of reef recovery.”

#clumsy #fish #works #harder